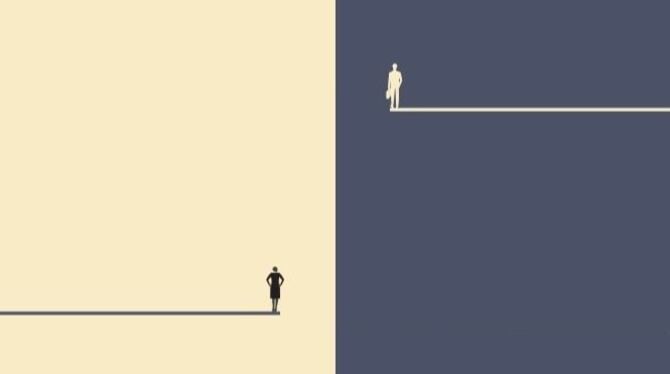

The gender wealth gap

Despite decades of debate and lobbying, the gender pay gap remains a problem internationally. While progress has been made, particularly in women’s access to coaching and leadership roles, deeper structural inequalities embedded in the workplace continue to widen disparities in wealth accumulation, especially in retirement. Marianne Curphey investigates.

This article is taken from the Summer 2025 issue of

Think Global People magazine

View your copy of the Summer 2025 issue of Think Global People magazine.The gender pay gap affects not just current salaries for women, but their long-term savings, and significantly affects women’s retirement income and financial security. Addressing these disparities requires a number of measures, including targeted policy interventions, such as equal pay legislation, paid family leave, and pension credits for caregiving periods in order to promote equitable retirement outcomes for women. For companies with international teams and those wanting to nurture women’s leadership and promotion, the issue of the gender wealth gap is particularly pressing.This is a subject which was hotly debated at our conference for International Women’s Day, which looked at workplace policies and actions we could all take to support women and girls progress in their careers and reach their full potential.

Pension wealth disparities

As an example, the European Journal of Population Study Pension Wealth and the Gender Wealth Gap (2022)provides a comprehensive analysis of pension wealth disparities between men and women across Germany. It identifies significant gender gaps in statutory, civil, and occupational pensions, with occupational pensions showing the largest disparity (41.8%). The study attributes these gaps to differences in labour market participation, earnings, and the types of employment contracts held by men and women. While the relative raw gender wealth gap is about 35% (or 31,000 euros) when analysing the standard measure of net worth, it shrinks to 28% when pension wealth is added, the study reports.In the UK, Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) published a report in March 2023 on The Gender Gap in Pension Saving,examining the differences in pension incomes and savings between men and women. It highlighted that while the gap in state pension income has narrowed, significant disparities remain in private pension savings, primarily due to differences in earnings, employment patterns, and caregiving responsibilities.“Women – who have lower lifetime earnings on average and have retirements – are likely to continue to have lower retirement incomes than men,” the IFS report says.Lower earnings potential

Sam Bourgi, an analyst at Investors Observer,argues that the issue is not just what women are paid now — it is how the cumulative effects of inequality affect their entire financial lives. In his analysis of women’s earnings and lifetime wealth in the US, he has uncovered major disparities in the financial fortunes of men and women.“Leadership and promotional barriers, maternity leave, and salary negotiations are among the costliest inequalities for women,” he says.“Wealth accumulation in the stock market is also a reflection of lifetime earnings potential,” he notes. “Since men have higher lifetime earnings than women, on average, they can invest more money in the stock market, which results in a much larger portfolio when it’s time to retire.”The roots of this disparity stretch back to leadership barriers, wage negotiation gaps, maternity leave, and the often invisible cost of unpaid care work — all disproportionately borne by women. Research by Investors Observer found that Women lose $1 million in retirement wealth due to the gender wage gap in the US.Underrepresented at board level

The Department for Work and Pensions published a report on the Gender Pensions Gap in Private Pensionsin June 2023 and found that women’s private pension pots in Britain are typically worth 35% less than those of their male colleagues by the time they reach 55.Equally in the US, Sam Bourgi says that there has been a noticeable failure to close the gender pay gap, despite women’s increasing presence in high-paying industries.“Women are increasingly present in high-paying roles and sectors, but they are still underrepresented in C-suite roles,” he said. “The gap is wider at the very top, especially in highly competitive roles. It could be because these roles “penalise” care work and career interruptions, which overwhelmingly impact women. It is usually women who take maternity leave, give up paid work to stay home with children, or take care of elderly parents.”He believes that there are also social and structural issues here which make it difficult for many women to contemplate a C-suite position.“Our society is not structured in a way that promotes family formation,” he says. “Anxiety over taking maternity leave and wondering about the future of your job and career progression because you have a child is a symptom of a much deeper societal issue.”Eroding earning potential

One of the biggest issues that goes unnoticed is that women are far less likely to negotiate a competitive salary. This so-called “negotiation gap” can erode women’s lifetime earnings potential, especially considering that average salary increases in the US are between 3% and 4% annually. For example, a position with a salary range of $100,000 to $120,000 USD can lead to very different financial outcomes for someone who took the lower end of the range than someone who negotiated the very top payout.Yet with women contributing only slightly less than men (6.2% versus 6.6%) towards retirement, the really significant figure is the compounding effect of even small annual differences in retirement savings.“Even the smallest differences compound over a 40-year career and create large discrepancies during retirement,” Sam Bourgi says. “Although this difference only amounts to a few hundred dollars per year, it can dramatically reduce future wealth. However, the biggest disadvantage women face is taking mid-career breaks. For example, even a two to three year break from work could mean hundreds of thousands of dollars less in retirement due to missed compounded investment growth.”Since retirement contributions in 401(k)s and IRAs (in the US) are a fixed percentage of wages, women’s lower earnings and more frequent career interruptions translate into lower retirement savings over time, he says.How higher education could shift the balance

The positive news is that women are now over-represented in college and postgraduate studies (women outnumber men in college enrolments and graduation rates in the US currently). Despite the recent issues college graduates face in finding commensurate employment, the research suggests that workers with a Bachelor’s degree or Master’s degree have significantly higher lifetime earnings than those who only complete high school.However, in order to help women secure a more financially secure retirement, government intervention may be necessary. Some potential policy fixes are government matching or top-ups for low-income earners, universal retirement accounts that allow for government and employer contributions during unpaid leave, and caregiver credits that acknowledge unpaid labour. However, it bears mentioning that these programmes can be controversial in the US, especially with such a large fiscal imbalance.“Career interruptions directly impact women’s lifetime earnings and, therefore, their lifetime retirement savings,” Sam Bourgi says. Government matching or top-ups, universal retirement accounts, and caregiver credits could potentially mitigate the impact.How to redress the balance

One of the key issues is that global companies have opaque or inconsistent pay across jurisdictions, sometimes for the same role.“It is common for companies to offer different pay packages for the same role depending on local norms,” he says. “To prevent the gap from widening, companies with global teams should standardise mobility policies (including pay) and apply them consistently across genders and .”Conversely, the public sector has one of the narrowest gender pay gaps, given the standardised pay scales, greater transparency in compensation, stronger benefits and paid leave, and more predictable promotion tracks.“The private sector could probably apply some of these lessons in creating transparent and predictable pay structures,” he says.The importance of financial literacy

Financial literacy plays a crucial role to lifetime financial security and wealth, yet access to investment education remains uneven. Those who understand how to maximise 401(k) contributions and employer matches are better equipped to prepare for retirement in the US. Bourgi stresses the importance of consistent saving and long-term planning — areas where gaps in knowledge can have lifelong consequences.“People who are financially literate are more likely to invest, save consistently, and plan for the long term,” he says. “They are also more likely to maximise 401(k) contributions, which play a significant role in preparing oneself for retirement. Understanding how to maximise 401(k) contributions can ensure that workers do not delay saving for retirement or leave employer contributions on the table.”Economic shocks, too, have gendered consequences. Women are overrepresented in sectors that are more vulnerable to downturns, such as retail, hospitality, and caregiving. During the COVID-19 pandemic, women experienced a disproportionate share of job losses in what became known as the “She-cession,” driven by school closures, childcare shortages, and unpaid caregiving responsibilities.Rethinking the world of work

The current retirement system favours linear, full-time employment, Sam Bourgi says, and acknowledges very little about non-linear career paths due to maternity leave, child rearing, or other forms of unpaid care.He argues that pension formulas should not just focus on “highest earning years” or “total years of service,” but should also factor in real-life circumstances that may require people to pull away from full-time work. Traditional planning also overlooks longer life expectancy (especially for women), greater likelihood of part-time work, and out-of-pocket health costs during retirement.However, it is unclear whether workplace structures can accommodate anything but the status quo at the moment, he says. So how can public discourse move beyond salary comparisons to address the broader, compounding effects of income inequality on lifetime wealth accumulation and intergenerational financial security for women?“It begins by having an honest conversation about what kind of society we want to have — one that encourages family formation and teaches the value of unpaid work (e.g. taking care of children and the elderly), or one that treats everyone like a robot on a treadmill progressing from point A (age 22) to point B (age 65),” he says.He urges companies and policymakers to think beyond linear employment models and understand the different pressures and components of women’s careers.Companies with globally mobile teams also have a role to play in addressing gender pay disparities. The challenge is not simply closing a gap on a spreadsheet, it is about reimagining a world of work that values every stage of life equally and recognises that women’s careers are often non-linear and involve breaks for caring and family responsibilities.Progress in the UK and Europe

Over recent decades, the gender pay gap in the UK and Europe has narrowed significantly, reflecting changing labour market structures, growing public awareness, and a series of legal and policy interventions. However, progress has been uneven and slow, and the persistence of the gap reflects both structural and cultural challenges that have yet to be fully addressed.Read related articles

- Taking action to accelerate inclusion and gender equality in the workplace

- International careers: are women assignees losing trust in EDI policy and practice?

- Encouraging the best in everyone in the workplace and supporting women and girls in fulfilling their potential

In the UK, one of the most visible drivers of progress has been the 2017 introduction of mandatory gender pay gap reporting for companies with over 250 employees. This legislation has improved transparency and placed reputational pressure on firms to address disparities in pay and representation. Since the introduction of the reporting requirements, the Office for National Statistics (ONS) has noted a gradual decline in the median pay gap, which stood at 7% in 2024, down from 9.1% in 2017. While modest, this represents progress, especially when viewed alongside increasing female representation in senior roles, particularly in the public sector and some corporate boards.Across Europe, EU-wide initiatives have also pushed member states to act. The European Commission’s Gender Equality Strategy 2020–2025 has set the addressing of the gender pay gap as a key goal, and the forthcoming EU Pay Transparency Directive, adopted in 2023,aims to extend transparency obligations and empower workers to challenge pay discrimination. It requires employers to disclose salary ranges in job advertisements, provide employees with information about pay levels and criteria, and explain any pay differentials between male and female workers. Under the new rules, EU companies will be required to share information on salaries and take action if their gender pay gap exceeds 5%.Several European countries have gone further. In Iceland, where equal pay laws are more rigorous than most, companies are legally required to prove they pay men and women equally for the same work — or face fines. Nordic countries more broadly have seen some of the narrowest gender pay gaps in Europe, thanks in part to strong welfare states, subsidised childcare, and widespread take-up of shared parental leave.In contrast, countries in Southern and Eastern Europe often show smaller headline pay gaps, but this can be misleading, as it sometimes reflects lower female labour force participation or occupational segregation, rather than genuine pay equality.One important area of progress has been in education. Across Europe, women now outnumber men in higher education attainment, which has led to increased participation in professional sectors. This educational advantage is starting to shift patterns in some industries, particularly in the younger workforce. However, the so-called “motherhood penalty” continues to exert a significant influence, with women more likely to reduce working hours or drop out of the workforce following childbirth — a trend that continues to widen the pay gap with age, according to a recent report by PWC.Progress has also been hindered by the persistence of part-time, low-paid work, in which women are overrepresented. Structural reforms — such as improving access to affordable childcare, increasing flexibility in senior roles, and embedding salary transparency — remain crucial to closing the gap entirely.While the UK and many European nations have made tangible progress, the gender pay gap remains a complex issue that will require both cultural change and stronger legal frameworks in order to support the career aspirations of women and girls.

| You can catch-up on several related workplaces themes from the latest Think Global Women event, including video highlights and a full range of resources here. |

Find out more about the Think Global People and Think Women community and events.

Subscribe to Relocate Extra, our monthly newsletter, to get all the latest international assignments and global mobility news.Relocate’s new Global Mobility Toolkit provides free information, practical advice and support for HR, global mobility managers and global teams operating overseas.

©2025 Re:locate magazine, published by Profile Locations, Spray Hill, Hastings Road, Lamberhurst, Kent TN3 8JB. All rights reserved. This publication (or any part thereof) may not be reproduced in any form without the prior written permission of Profile Locations. Profile Locations accepts no liability for the accuracy of the contents or any opinions expressed herein.